Nowadays, there are many people practicing traditional Tai Chi worldwide—reportedly several hundred million. As a representative of Chinese cultural heritage, Tai Chi has also been honored as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Such large numbers and market scale are indeed gratifying. It’s certainly a good thing that the valuable practices left by our ancestors benefit more people.

From a health and wellness perspective, the value of Tai Chi is unquestionable. However, as a martial art, today’s Tai Chi has strayed from its martial roots, becoming unrecognizable and far from authentic.

With the widespread promotion of Tai Chi, there are very few who can truly be said to practice “traditional Tai Chi.” Those who master the traditional skills are even rarer.

The reason for this is simple: although many people practice Tai Chi, very few truly study what “Tai Chi” is. Many believe that knowing a few routines constitutes Tai Chi.

Because of this, today’s Tai Chi is often ridiculed as “Tai Chi exercises.”

In fact, many who mock others for practicing “Tai Chi exercises” are not much better themselves.

The real situation of Tai Chi is this: 99% of Tai Chi practitioners do not understand what Tai Chi is, let alone what “Tai Chi Chuan” (Tai Chi boxing) is.

The greatest tragedy in the Tai Chi community is misleading others and oneself; true heritage is on the brink of being lost.

At this point, some may ask, “Does the author’s theory constitute the correct interpretation?”

Yes, what I say might not be entirely correct either; it’s just meant to spark discussion.

However, I must say that if we don’t face the question of “what is Tai Chi,” Tai Chi Chuan will be finished.

The reason we add “Tai Chi” before “Chuan” is that the cultural connotation of “Tai Chi” is the foundation and essence of the martial art. Without it, the martial art cannot be called Tai Chi Chuan.

Of course, we must neither lose the original meaning of Tai Chi nor deviate from the principles of martial arts. It is incorrect to favor either side exclusively.

What Exactly Is Tai Chi?

The term “Tai Chi” originates from the ancient traditional “I Ching” (Book of Changes), and it is also an important theory in Taoist philosophy. Many people have a superficial understanding of the term from books or hearsay, and without the oral transmission from a knowledgeable master, it is easy to misinterpret it.

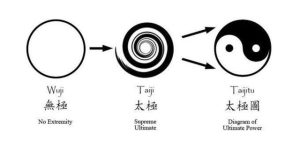

Most people think “Tai Chi” represents yin and yang or is synonymous with “yin-yang,” but that is not correct.

“Tai” means “big,” with an extra stroke below, and “Chi” means extreme. In simple terms, “Tai Chi” means reaching the extreme. Since nothing can reach the extreme instantly, “Tai Chi” represents a process of change, from one to three, and then to myriad things.

Thus, the beginning of Tai Chi is “Tai Yi,” and reaching the extreme is “Tai Chi.”

The process from “Tai Yi” to “Tai Chi” is a journey from small to large.

If we understand Tai Chi as the “extreme,” we can see that this extreme is a result of change. This change is the process of yang reaching its peak and becoming yin, and vice versa.

Where does Tai Chi come from?

If Tai Chi is “acting with no action,” then you must start with “inaction,” which means “inaction but nothing remains undone.” This “inaction” is “Wu Chi.” Hence, ancient texts say, “Tai Chi is born from Wu Chi.”

In simple terms, Tai Chi is born from Wu Chi. Without Wu Chi, there is no Tai Chi.

What is true balance? It is the combination of Wu Chi and Tai Chi; because Wu Chi represents yang, and Tai Chi represents yin.

Thus, Wu Chi is “yang in motion and void,” which is invisible, while Tai Chi is “yin in stillness and solid,” which is visible.

This principle is like why a balloon can fly—it is filled with air. The air is invisible, but we believe in its existence, which is Wu Chi. The process of the balloon inflating and becoming elastic, then flying, is the change to the extreme, which is Tai Chi.

Therefore, the beginning of “Wu Chi” is “Tian Yi.” “Tai Yi” and “Tian Yi” are also referred to as “Tai One” and “Tian One”; “One” is the Dao of yin and yang. “Tian One” is the concept of “Heaven and man as one,” which is the basic idea of the “Wu Chi” state.

All things achieve true yin-yang balance with both Wu Chi and Tai Chi. Thus, neither Tai Chi nor Wu Chi alone represents yin-yang; rather, yin and yang are their foundation and interdependent.

Anything that reaches its extreme will change—this is the principle of extremes. Therefore, Tai Chi also seeks “balance,” which requires the foundation of “Wu Chi,” much like the principle of a balance scale.

Understanding this, you realize that seeking yin-yang balance solely through practice is misguided, as yin and yang are the results of change. Often, when we hear about “keeping the One,” it means maintaining both Wu Chi and Tai Chi.